Isolation in database technologies is fundamental to ACID — Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability. Isolation refers to the ability of a database system to keep transactions separate from each other during concurrent execution. This means that the operations of one transaction are visible to other transactions only after they are completed. The primary goal of isolation is to maintain data integrity by ensuring that concurrent transactions do not interfere with each other.

Higher isolation levels reduce the risk of data errors but often come at the cost of reduced performance due to increased locking and decreased concurrency. This article discusses the anomalies that can occur if you use PostgreSQL at the SZ isolation level. We also share our practical experiences with solving the anomalies in our high-volume tables and how we restored our system to zero serialization errors.

What are serialization anomalies in PostgreSQL?

For stateful services, sometimes the application semantics require SZ for correctness, and sometimes we use it just because it simplifies reasoning about correctness. For example, PostgreSQL Docs state that:

“Consistent use of Serializable transactions can simplify development. The guarantee that any set of successfully committed concurrent Serializable transactions will have the same effect as if they were run one at a time means that if you can demonstrate that a single transaction, as written, will do the right thing when run by itself, you can have confidence that it will do the right thing in any mix of Serializable transactions, even without any information about what those other transactions might do, or it will not successfully commit.”

However, using SZ in your database transaction means your transactions may fail due to serialization errors. Generally, this is a desirable feature for correctness. However, sometimes transactions fail even when they should not. Such false positives, or anomalies, occur when the database thinks the concurrent transactions are not serializable. However, in reality, they are serializable. PostgreSQL Docs do warn about this behavior but give no solutions.

“Applications using this level (SZ isolation level) must be prepared to retry transactions due to serialization failures.”

What can be the problem if serialization anomalies can be dealt with by persistently retrying them until they succeed? Well,

- A large number of serialization errors lead to unnecessary, and sometimes preventable, retry attempts that increase the load on the database and effective latency of queries.

- In the case of highly concurrent workloads, there is no guarantee that transactions will succeed after any bounded number of retries, so there’s a risk of failure due to retry exhaustion, which is undesirable.

Unfortunately, this was the exact scenario we faced in production!

Our PostgreSQL setup

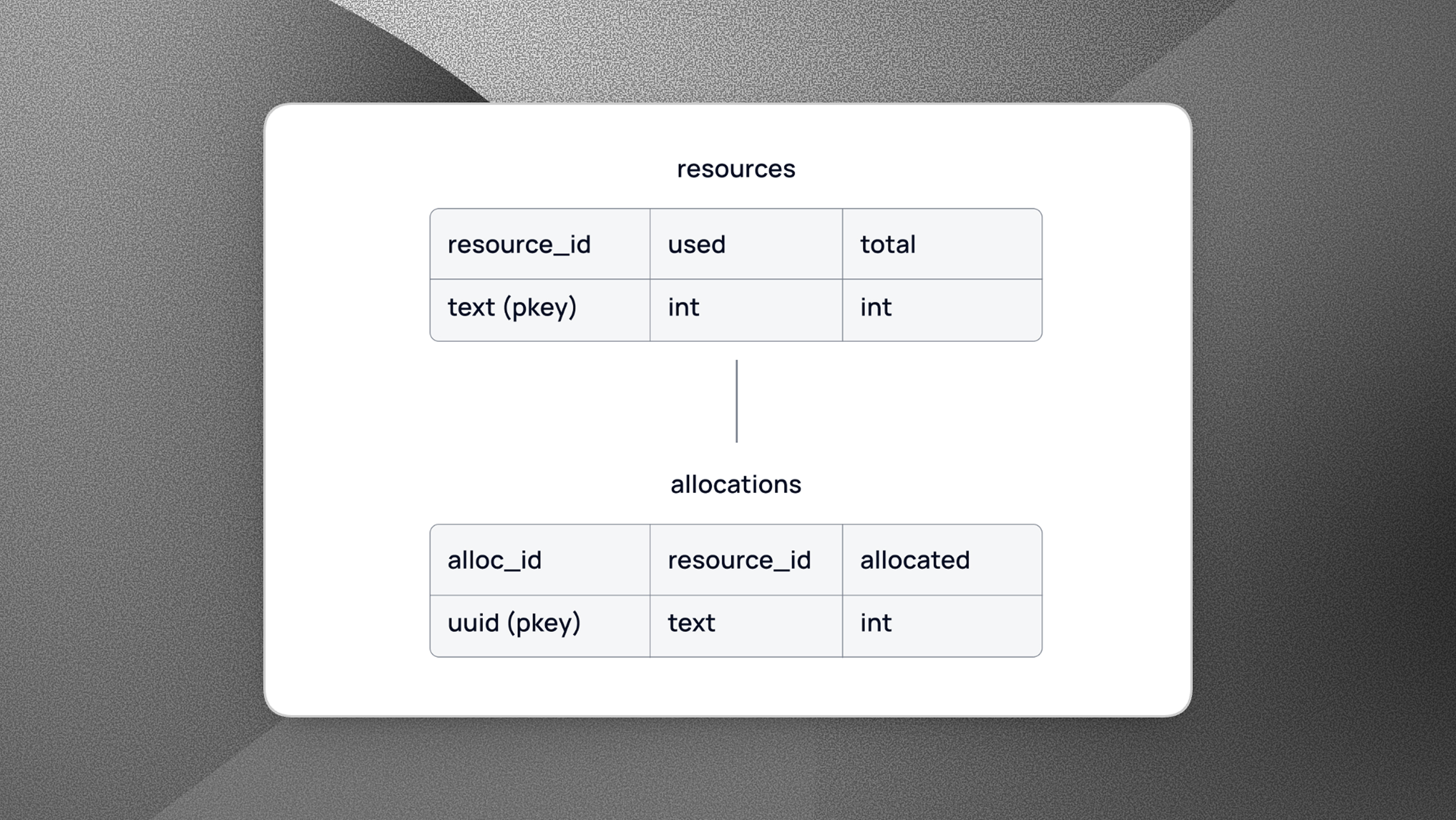

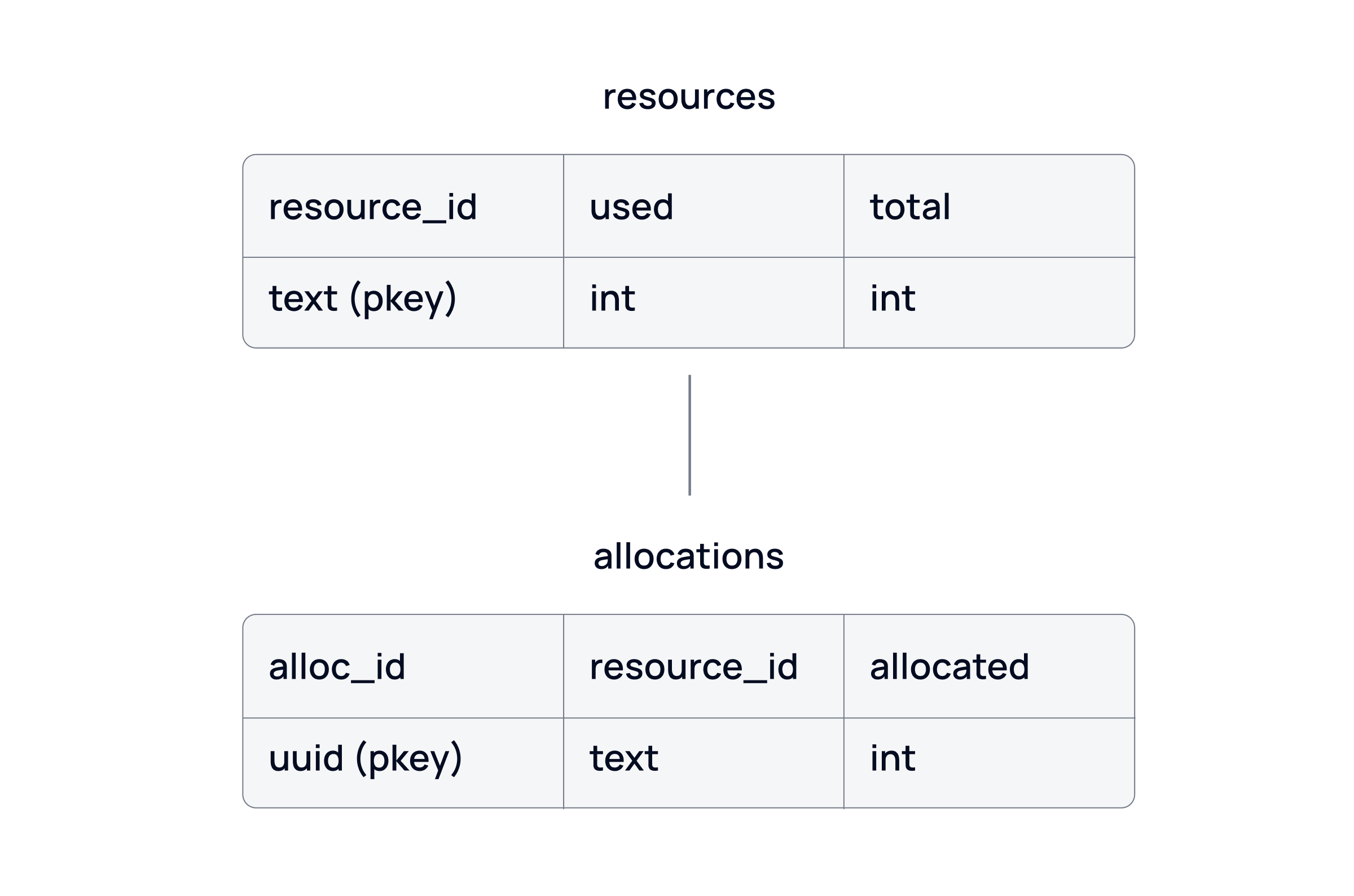

To avoid diving into the complexities of our actual data tables, we would like to present the table structures in a simplified format. Consider the two tables shown below. The first table records resources and tracks their usage & total capacity. Any resource allocations must be registered with the second table in a transaction so that both tables are consistent.

The sum of all allocations for a resource_id in the allocations table must match the value of the column used in the resources table.

The example may seem a bit artificial. After all, the resources table, as defined above, is simply an aggregate view of the allocations table. Having two separate tables seems superfluous. However, we share this simplified table setup to keep the article focused on the serialization solution.

Consider running the following transaction concurrently on the table.

The above transaction takes three inputs:

- resource_id

r, - allocation_id

i - count (to allocate

x).

It tries to insert the new allocation with id i into the database, but only if it does not already exist. If it exists, then it updates the existing allocation. As you can observe, an interleaving of transactions can cause the resource table and allocations table to get out of sync without serializability. So, we run all transactions in SZ.

#Anomaly 1 — Errors double the number of requests

In our system, we wrapped a transaction similar to the one described above in a retry block with an exponential backoff after 30 retries. We then wrote a clever stress test to verify concurrency behavior. We observed some serialization errors, but there was nothing that a few retries could not solve. Confidently, we released the query to production to experience the actual load.

We knew serialization errors were possible. After all, if resource_id is the same for several transactions, and they all try to update the same resource row concurrently, then some of them are sure to fail. However, we anticipated the number of failures to be too low to cause any impact. Particularly because we know that our transactions are going to be such that each transaction is guaranteed to have a unique allocation_id i.

On the first day in prod, we observed over 1M requests and … 1.9M serialization errors! Yes, the number of errors was nearly double the number of requests, suggesting that, on average, every request was being retried. Worse, approximately 1000 transactions failed completely after exhausting all their retry attempts (over 30!). The failed transactions were causing serious errors.

Luckily, the magnitude of errors was unexpected, but the cause was well-known.

Our solution

One solution to such a scenario is to acquire an explicit row-level lock on the resources table and run pessimistic, locking-based concurrency. It is a concurrency control method where a transaction locks the row it needs to access right at the start and holds the lock until the transaction is complete. It is “pessimistic” because it assumes the worst-case scenario where conflicts are likely.

However, in the end, we implemented a far simpler solution. We used an in-memory mutual exclusion (mutex). A mutex is a programmatic way of ensuring that only one thread can access a particular code module or data at a time. Our solution worked because our service was singleton — with only one instance throughout the application’s lifecycle. This means that all requests to the service are funneled through this single instance, making an in-memory mutex a viable solution for concurrency control. We also strengthened our in-memory stress test suite and verified no serialization failures could be detected.

#Anomaly 2 — Failing transactions

Once we resolved the first anomaly, we grew more confident and reduced the maximum number of retry attempts from 30 to 10. Again, we released the new version to production. Serialization failures reduced significantly BUT DID NOT STOP! We were now seeing a failure rate of <2% but this was still enough to exhaust all ten retries of 100+ requests. Typically, we could have just increased the number of retries some more and called it a day, but something was unsettling about why the transactions would fail when they should not. It was clear that we did not understand something.

Debugging the anomaly

We started digging into the internals of SZ, and after scouring through multiple documentation pages, StackOverflow & DBA SE Q/As, we discovered some previously missed details about predicate locks. Apparently, to make SZ work, Postgres has to keep track of the set of rows read by a transaction (on top of tracking the set of rows written by the transaction which it anyways does in other weaker isolation levels).

To do this, Postgres acquires what is called a SIRead lock on the rows it reads (or the whole table or the index page, depending upon the granularity of the read). We realized intuitively that concurrent transactions could conflict if they hold opposite read & write locks on each other’s rows. Note that the SIRead lock is not a read lock in the traditional sense. It is not even a lock at all — the term “marker” would be more appropriate. However “SIRead lock” is the term used officially so we have used the same in this article.

Thankfully, Postgres lets you inspect all the locks it acquires through the pg_locks system table. As part of the debug process, we constructed two concurrent transactions in various ways to study the locks Postgres declares through pg_locks.After a day, we hit the jackpot. We discovered a pair of transactions that, when run in an interleaved fashion in a particular way, always resulted in a SZ failure. The interleaving looks something like this:

This interleaving conflicts deterministically whenever one of i1 or i2 does not exist in the allocations table.

We thought this was strange and were somewhat surprised, mainly because these did not conflict when the rows existed in the table. After all, both the allocations have a different id and should be serialized in any order. Why then would Postgres fail the last one to commit, pleading a read/write dependency conflict?

To find an answer, we looked into the pg_locks table at each step. We observed that Postgres places an SIRead lock on the whole table instead of on the row, when there is no row to lock in the first place. Based on our observations, we (incorrectly) reasoned that when a row is absent, Postgres has to take a SIRead lock on the whole table, and once you have a lock on the whole table, the conflict is inevitable. This was a false positive, and we now know why!

Our solution

To fix it, we did the following.

- Adapted our stress test suite to highlight the interleaving scenarios more until we started seeing serialization failures again in our test suite.

- Changed our transaction so that the SELECT is now performed outside of the transaction (in a read-only transaction)

- Employed an in-memory serialization technique to still ensure that no other transaction could insert a row in-between.

The reasoning was that if there’s no select statement to return empty rows, a SIRead lock on the whole table was impossible, and the problem would be solved. Our test suite was green again. With the latest change, the new serialization errors promptly disappeared, and we had a clean output again. Elated, we released it to production.

#Anomaly 3 — Persistent failures despite query changes

The latest change did … nothing. The rate of failures did not even budge. How could it be? A deterministically conflicting transaction on our local machines and our test suite responding positively to the fix and yet no success on real production?

After more unsuccessful debugging attempts, we finally decided to read up more on the SZ isolation level. The Postgresql docs refer to their implementation based on the Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI) technique. This is a technique to essentially derive serializable transaction semantics from a system that supports snapshotting (like Postgres’ MVCC). Snapshotting is just another jargon for Repeatable Read (RR).

Limitations in PostgreSQL implementation

The linked paper goes into all the details, and is a surprisingly friendly read. For the sake of this discussion, we distill the essence of the paper. Finding serialization anomalies means finding a cycle in a graph that maps read/write dependencies among concurrent transactions. However, finding the cycle is a complex, resource-intensive task, so with some cleverness, the paper demonstrates a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for a cycle to occur. Because the condition is only necessary, and not sufficient, any implementation relying on it is bound to give false positives as it may think that a cycle exists when it does not. False positives do not influence correctness, only performance, and in conjunction with multiple additional false-positive mitigation optimizations that Postgres employs (described in the paper), the implementers found the trade-off too good to give away.

So what we faced was not a false positive (well, it was, but not due to what we thought as anomaly 2). Instead, it was an artifact of how predicate locks are implemented. It turns out Postgres does not take predicate locks on the result set of a query, but on all the rows it has to scan to reach the query row.

Reason behind re-occuring failures

In particular, if the query planner can choose one of the two to discover your result set

- SeqScan. If used, the SIRead lock ends up locking the whole table — even if you can prove via a unique constraint that there could have been at most one row in the result set.

- Index scan. If the row is not found during an index scan, Postgres locks the index page on which the row would have been.

Now, the query optimizer is its own beast. It chooses to do a SeqScan for a primary key if it thinks that will be faster. And unknown to us, that was happening in our local systems. The allocations table in our local systems was so small that an ordinary select statement would consistently regress to a SeqScan instead of a Unique Index lookup under certain circumstances. This caused too wide SIRead locks and high SZ failures which we observed previously. This is also why our previous fix worked on local, but did not work on production. In production, the table has 10M+ rows, and no sane query planner would choose a SeqScan. Always an index scan, so always row-level or page-level locks, which have a much lower probability of conflict.

However, the higher failure percentage was due to the SeqScan on the resources table. Yes, even in production, the resources table was small (about ten rows), and it was meant to be small. Query planner seems to randomly flip-flop between choosing a SeqScan vs. Pkey-scan on the smaller table (still unknown to us why). We reasoned that whenever it chooses a SeqScan we see an SZ failure.

We verified our hypothesis by temporarily stuffing the resources table in production with many fluff rows to force the planner to choose index lookup over SeqScan. The SZ failure rate dropped overnight to a staggering 0.001% (still not 0!) largely confirming our hypothesis.

Final solution

But our reading of the paper also suggested a better solution. We now understand that the only difference between RR and SZ comes from using SIReadLocks (to track rw-anti dependencies in paper-speak) to detect potential cycles. A surprising revelation from the paper was that a read-only RR can never fail because it holds no locks to conflict, but a read-only SZ can fail due to genuine anomalies. The absence of SIRead locks makes RR weaker and prone to SZ anomalies. However, if the transaction is designed in such a way so that all rows that are read are also written to (or updated), then RR is no weaker than SZ because it misses no locks (indeed even SZ promotes SIRead Lock to a full Exclusive Lock upon a write to the same row, so no SIRead Locks linger past the COMMIT of such SZ transactions).

Our transactions are implicitly of such a nature, as we update the same row in the allocations & resources table, which we attempt to read (even if unsuccessful). Thus, we could safely downgrade to RR without compromising on any SZ guarantees and enjoy the simplicity of MVCC. Since our change, we have not seen a single SZ failure in our system.

Conclusion

This was our journey from 1.9M failures to zero. Some final observations.

- Choosing SZ by default for your transactions simplifies reasoning at the application level, but under high volumes, serialization failures can become a real nuisance, not simply solvable through “more” retries. The trade-off is essential.

- We made the mistake of assuming failures reproducible locally were the same as those happening in production. As we later realized, query planners may choose drastically different plans and system configurations could also be so different, making reproducing failures a challenge.

- When using SZ, remember that predicate locks are acquired on all the rows scanned rather than just the result set. Queries that scan large portions of the table or too small tables are not good candidates for this isolation level as they lead to higher number of conflicts.

- Read-only SZ transactions may also fail due to real serialization anomalies (not just false positives). In our application, we discovered at a few places we were starting a read-only SZ transaction reading rows from multiple tables but then aborting the transaction if the read values were not meaningful. The reads can not be considered serialized until the transaction commits successfully.

Ultimately, reducing serialization errors may require query redesign so you can use PostgreSQL in Repeatable Read mode — like we did!